Young Climate Prize alumni participate in Climate Film Festival panel

Three members of our first Young Climate Prize cohort shared the different ways in which design has guided their climate activism, as part of a conversation during NYC Climate Week 2025.

By Dan Howarth

From left to right: Dan Howarth, Alfonse Chiu, Pamela Elizarrarás Acitores, and Joseph Nguthiru on stage at the Climate Film Festival. Photo by Emma Stolarski

On September 22, 2025, The World Around and the Climate Film Festival convened three members of the inaugural Young Climate Prize cohort—Alfonse Chiu, Pamela Elizarrarás Acitores, and Joseph Nguthiru—for a conversation on how design, language, and storytelling shape contemporary climate action. Moderated by The World Around’s director of editorial and strategy, Dan Howarth, the panel discussion traced the evolution of the prize and the benefits it offers to the 25 under 25s chosen for each cycle. The speakers, who each originate from a different continent and work across a wide range of practices—from curatorial practice and systems design, to material innovation and community-led entrepreneurship—represented a cross-section of approaches to tackling the climate crisis, which has affected each of them differently.

All three speakers reflected on how their work uniquely responds to specific local realities, while remaining deeply interconnected. Across the conversation, design emerged as a uniting method for building narratives, reshaping value systems, and fostering solidarity across generations. The panel formed part of the day-long Narrative Change Summit, organized by the Climate Film Festival and hosted at the SVA Theater in Chelsea during Climate Week NYC. Read on for an edited version of the transcript from the live event.

“Thinking through solutions through exhibition-making and social design is one of the instrumental ways we can change the narrative. And changing the narrative is about creating hope. I think that’s why we’re here”—Alfonse Chiu

Dan Howarth: It’s been an incredible journey to meet so many young people whose projects have evolved through the Young Climate Prize and beyond, especially through their work with mentors. It’s incredibly inspiring, and I feel very lucky to have played a small part in it. We wrapped up our second cycle earlier this year, with winners presenting at MoMA during The World Around’s annual Summit. We’re also launching Young Climate Stories this fall—a series of short documentary-style films that go much deeper into the fellows’ projects by visiting where they live and exploring how they’re working within their communities to take climate action.

To begin, could each of you introduce yourselves and share what first brought you into the climate movement? Alfonse, let’s start with you.

Alfonse Chiu: My name is Alfonse Chiu. I’m a Taiwan–Singaporean designer, writer, and curator. During my time with the Young Climate Prize, I was mentored by Paola Antonelli, senior curator of architecture and design at MoMA. The reason I got involved is quite simple. We live on Earth, and Earth is breaking apart. Thinking through solutions through exhibition-making and social design is one of the instrumental ways we can change the narrative. And changing the narrative is about creating hope. I think that’s why we’re here.

Pamela Elizarrarás Acitores: For me, the journey started when I was seventeen, so about 10 years ago. It began with the ocean plastic pollution crisis, when I was creating awareness campaigns in Mexico. The more I learned about the problem, the more I realized that the real culprit was the fossil fuel industry, not us as consumers. Yes, we can play a part in the solution, but we weren’t the source of the problem. That realization led me into the young climate justice movement, both in New York and internationally. From there, I became deeply interested in words and the language around climate action.

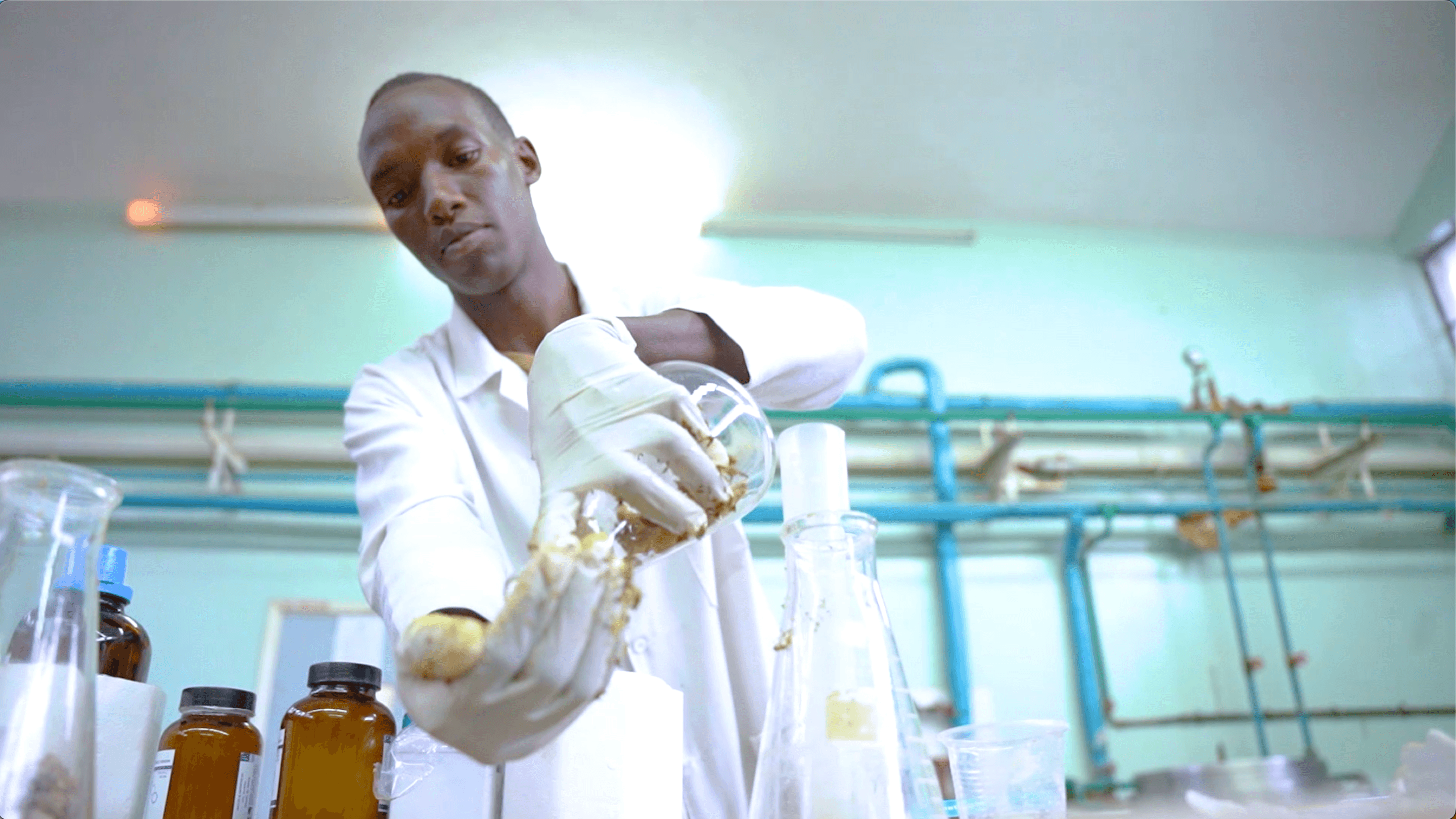

Joseph Nguthiru: My name is Joseph Nguthiru. I’m from Nairobi, Kenya, in Africa. I run two startups. One is called HyaPak, where we manufacture biodegradable plastics from an invasive plant called water hyacinth. The other is called M-Situ, where we use AI as an early-warning system to detect deforestation, wildfires, and charcoal burning. In Africa, we have a very different perspective on climate change. We have a young population—the median age is nineteen—and we face serious challenges around food insecurity and water insecurity. All of these are exacerbated by climate change. So the question becomes: what novel ideas can help us address climate change alongside the socioeconomic problems facing the continent?

DH: Joseph, could you expand a bit on the biodegradable plastics project and how design helps you shape and move it forward?

JN: We make products that look, feel, and perform like plastics, but they biodegrade at the end of a given timeline. They’re meant to replace low-density polyethylene—the low end of plastic packaging that we use in everyday products. We work with fishing communities that are affected by water hyacinth. They harvest the weeds, dry them, and then we carry out a chemical conversion process. In terms of pricing, we’re currently one of the cheapest alternatives to single-use plastics globally, and the quality of what we make is actually stronger than regular plastics. That’s where design comes in, by thinking about how to make the science as good as possible across the entire industry.

DH: Pamela, could you tell us more about Climate Words and how design thinking shaped that project?

PEA: Climate Words started after COP26, the UN climate negotiations. My co-founder Valentina and I noticed that many climate-related words were being taken out of context and used for greenwashing or political purposes—often to benefit individual agendas.

I remember wanting to grab those words back and say, “That’s not what the word actually means.” At the same time, we realized that climate literacy is directly correlated to climate action. The more people understand climate change, the more likely they are to take action. Climate Words is a lexicon—a dictionary of terms related to climate change—and every word is defined by a frontline expert. That means someone who understands the problem, but also the solution. The project is really about systems organizing and systems design.

DH: Alfonse, your work takes a more abstract, curatorial approach. How does that fit into the wider climate narrative?

AC: As a cultural worker and exhibition maker, design infiltrates every moment and everything I do. It’s present in the artifacts I choose to bring together, in exhibitions, programs, and screenings, and in the ways I construct narratives. I’m currently working with the Yale Center for Ecosystem and Architecture with professors Maite López and Anna Dyson on a test-bed exhibition and workshop in New Haven. I’m also continuing an independent research project that began during my time in the Young Climate Prize, which looks at solidarities that can emerge across pan-tropical biogeographies. For me, design is about relationships—how we create them, how we sustain them, how we live together. Design becomes an object, a subject, and a methodology.

From left to right: Joseph Nguthiru, Alfonse Chiu, Pamela Elizarrarás Acitores, and Dan Howarth

DH: Storytelling feels like a central thread in all of your work. How did the Prize, your mentors, and working with one another help you build your stories?

AC: The prize was incredibly formative for how I think about exhibition-making and solidarity. Before the Young Climate Prize, I was working on capacity development with Indigenous artists, designers, and filmmakers in Malaysia. That project paused while I was in graduate school and participating in the Prize, but now I’m thinking about restarting it as an archive of Indigenous knowledge—not for outsiders, but as capacity-building for the community itself. Narrative-building becomes central in asking how we communicate and how we work together.

PEA: My mentor during the prize was curator Mariana Pestana, and she really helped us think about structure. We didn’t want the words to live in rigid categories or themes. As a user, you might enter the lexicon looking for a word related to architecture, and end up learning about water, resilience, or resistance. Something else that was really special was the network itself. To this day, I value the collaboration and the support system that came out of the Prize.

JN: One of the key things I learned was that design, chemistry, and product-making don’t work in isolation. Storytelling comes from involving communities and people. If you’re an entrepreneur in the climate space, you want your products to be adopted. The only way people will choose climate-positive products over fossil-fuel-based ones is if they understand the story, the how and the why. Not just why fossil fuels are bad, but what we’re doing about it, what already exists, and how they can be part of it. In Kenya and Rwanda, single-use plastics are banned. So the question becomes: what alternatives do we give people, and how do we teach them about those alternatives?

DH: To close, why has the Prize’s cross-generational approach of working with mentors and across cohorts been important to you?

AC: It’s important to know there are people before us doing the same work. Otherwise, it can feel incredibly lonely, especially when you’re fighting against industries with enormous marketing budgets. Intergenerational collaboration builds continuity of knowledge, community, and care.

PEA: I grew up in youth climate justice movements where it felt like we were trying to solve the world on our own. Coming into the Young Climate Prize felt like a weight off my shoulders. There were people older than us who had already done similar work, and they were on our side. We didn’t need to fight them. We could work with them.

JN: Climate action needs integration. Water, language, design, plastics, energy, there are so many verticals that need to move together. The Prize creates that ecosystem. If we want a just transition and real adaptation to a changing world, collaboration across generations and disciplines isn’t optional.

Nominations are currently open for the Young Climate Prize Cycle 03, and applications will officially open on Earth Day, April 22, 2026. If you or someone you know has a self-initiated climate-action project, and would benefit from this unique mentorship and academy program, nominate them now!

If you or your company is interested in supporting or partnering with the Young Climate Prize, we'd love to hear from you.

Watch Young Climate Prize Videos

Hyapak

Climate Words

Thermotropicana